What is the relationship between the artist and the unconscious? What does it mean that the artist metabolises the unknown, and what bearing does this have to the rest of society?

In her homage work to Freud and psychoanalysis– Dreams 1900-2000: Science, Art, and the Unconscious Mind, art historian Lyn Glamwell writes: “Early-twentieth-century artists were quick to realise, as Freud himself had suggested, that the process by which the unconscious mind produces a dream—the dreamwork–is analogous to the process by which an artist creates metaphors and other symbolic forms.”

While I’m in agreement with Glamwell’s sentiment, what I think is neglected here is the notion that the reality outruns mere analogy. It may perhaps be more necessary to suggest that the artist actually enters into a reciprocal dialogue with the unconscious mind when in the midst of the creative process. The creative cast their nets deep into the mystery in order to haul aboard the pearls of inspiration; inspiration being only one of the many curious specimens that may be found in the depths. An interchange of conscious and unconscious content is conducted, a dance of diplomacy so to speak; a subtle call and response that stimulates somnolent concepts, forms and symbols to rise energetically to the surface of consciousness. Though, it is entirely possible for these latent energies to arrive on the page without passing through the window of awareness.

As C. G. Jung writes in his work The Spirit in Man, Art, and Literature:

“The unborn work in the psyche of the artist is a force of nature that achieves its end either with tyrannical might or with the subtle cunning of nature herself, quite regardless of the personal fate of the man who is its vehicle.”

It is necessary here to point out that this has been the principle from time immemorial. Not only since dada, surrealism; Breuer, Freud or Jung; but too, when the dawn generations of our species first met their cave walls with charred sticks and pigments; there was contact with the hidden paradigm that we now name the unconscious. Characterised throughout antiquity as the Muses, or divine inspiration; or in cultural anthropology as the ecstasy of shamanism; the unconscious is a multi-faced mystery that remains eminently shrouded in our age of scientific pragmatism.

However, due to the theoretical works of psychodynamic thinkers such as Freud and Jung, this principle was known intimately to the early twentieth century artistic movements of expressionism, dada and surrealism. Though arguably, the instrumentality of such reached its zenith within the epoch of the abstract expressionists. While the artists of dada and surrealism were successful to a degree in their attempt to depict certain contents of the unconscious; and the expressionists respectively, in distilling the subjectivity of experience, I believe it to be the abstract expressionists that came closest to touching the quintessence of the unconscious itself. This is due to their employment of the unconscious as tool and method, as opposed to merely inspiration or motivation.

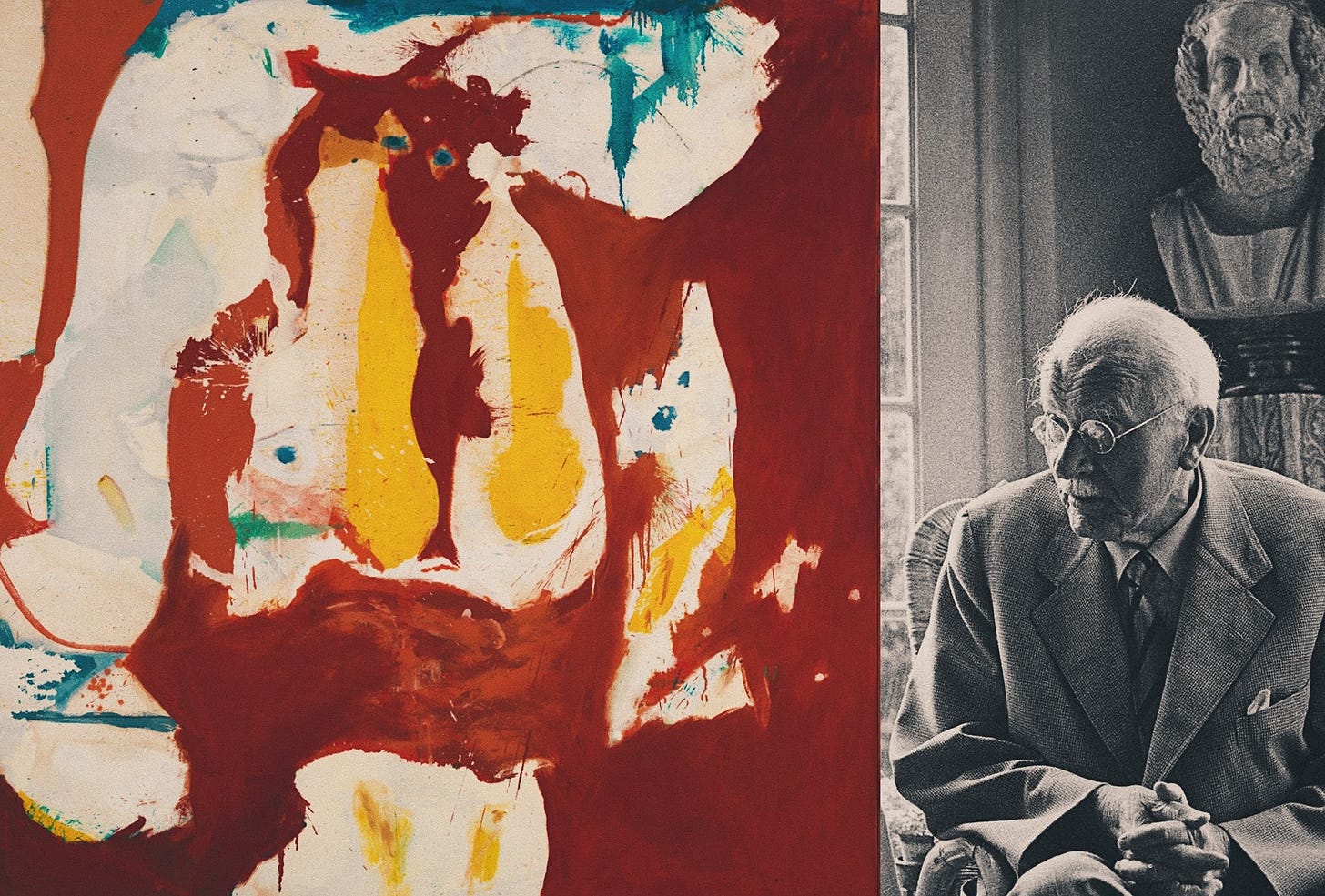

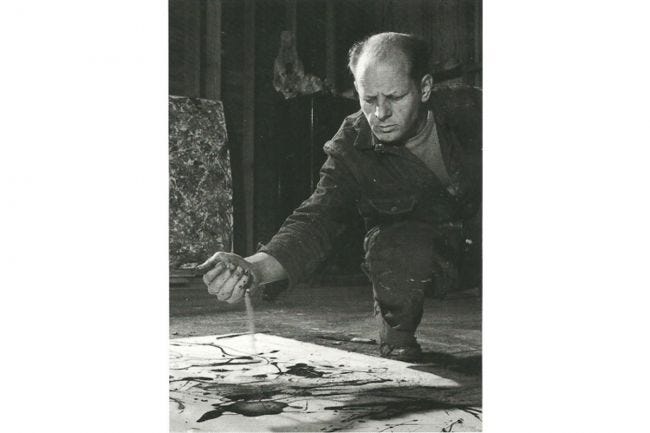

The spontaneity so intrinsic to the work of artists such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning resulted in uniquely expressive and highly idiosyncratic paintings. The speed of mark making and thus the element of chance that was inherently introduced minimised the degree of conscious control the artists had over the finished work. This in turn allowed for a more nuanced and symbolic representation of the artists’ psyche, that prioritised depicting their emotional, psychological and unconscious realities over figurative or pictorial forms.

While the fields of art and psychology have always been implicitly connected and somewhat symbiotic, it wasn't until the psychoanalytic school began releasing its paradigm shifting theories that they became explicitly comparative. When Freud postulated his hypotheses of the dynamic, economic and topographic perspectives of the unconscious, a new language of the human condition emerged and thus a new zeitgeist of human self reflection began. The artists of the early twentieth century were among the first to embrace this new way of conceptualising themselves psychologically, emotionally and creatively.

For the abstract expressionists, Freud's theory of the unconscious provided a framework for deeper self examination, and interrogation of the hidden aspects of the individual’s psyche, that would inevitably prove as a perennial wellspring of creative potential and inspiration. It could be argued that this active engagement with the unconscious became the foundation of the abstract expressionist movement, as it rooted itself deeply in subjectivity and individualism; thus laying a bridge firmly between modernism and postmodernism.

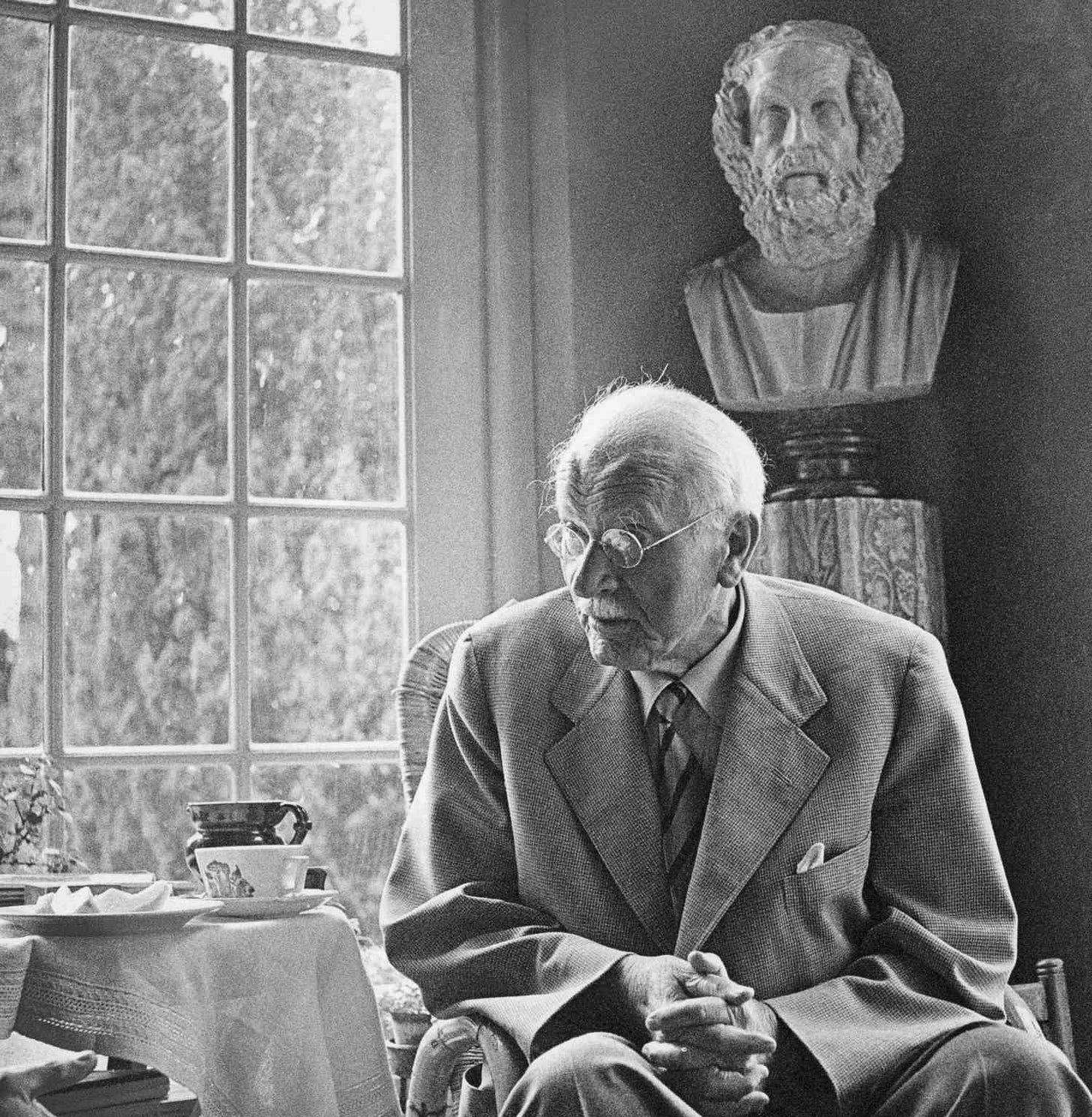

Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung’s theories of the unconscious expanded exponentially upon the foundations laid by Freud. Jung was concerned with the universal aspects of human psychology, and postulated concepts such as the collective unconscious— the notion that beyond the personal unconscious is a ‘phylogenetic substratum’; a hidden repository of human experience that gives rise to mythology, symbols and archetypes.

Jung would write in Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious:

“In so far as man is born totally new, but continually repeats the stage of development last reached by the species, he contains unconsciously, as an a-priori datum, the entire psychic structure developed both upwards and downwards by his ancestors in the course of the ages. That is what gives the unconscious its characteristic ‘historical’ aspect, but it is at the same time the sine-qua-non for shaping the future.”

Embedded within this quote is Jung’s psychological interpretation of Ernst Haeckel’s 1866 coinage ‘Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny’. This is the theory in evolutionary biology that an individual organism, in the course of its development, goes through all the stages of those forms of life from which it has evolved. While Jung did not infer this in a literal manner, he saw its parallel reflected in the development of the psyche; stating:

“The modern individual retains traces of the primitive mind– both intuitive and savage— in his consciousness.”

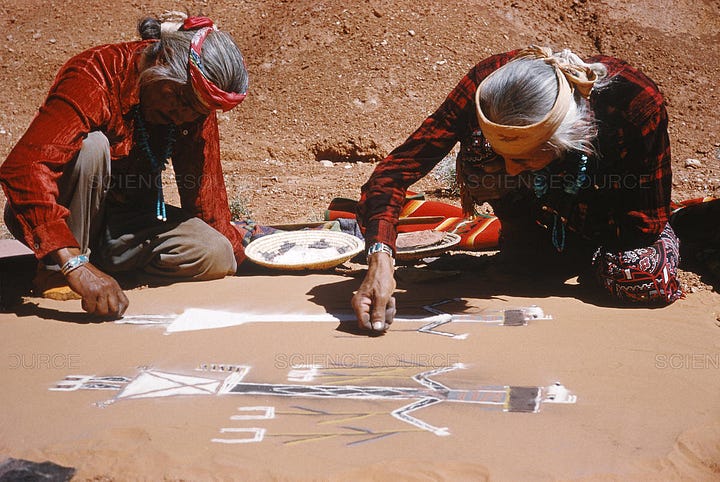

The abstract expressionist painters would certainly lean into this archaic modality. Particularly within the practice of action painting, as it could be comparative to tribal or ecstatic shamanic activity; evoking the unconscious through intuitive gestural movement and symbolic representation. However, colour field painters Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb and Barnett Newman would write to senior New York Times critic Edward Alden Jewell in 1943, stating: “Since art is timeless, the significant rendition of a symbol, no matter how archaic, has as full validity today as the archaic symbol had then.” and “We assert that the subject is crucial and only that subject matter is valid which is tragic and timeless. That is why we profess a spiritual kinship with primitive and archaic art.”

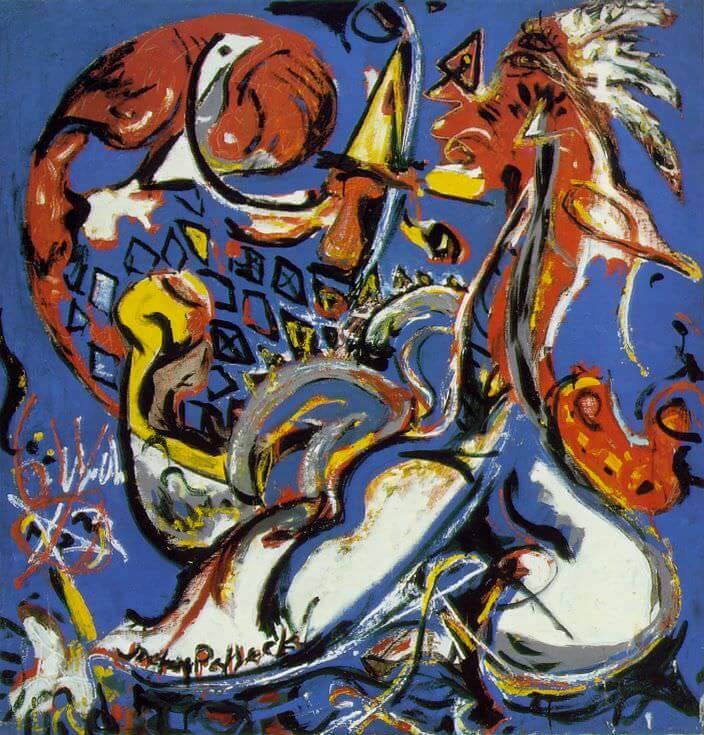

Intimations of this spiritual kinship may also be found in the way Jackson Pollock’s methodology and certain thematic elements were partly inspired by the sand painting rituals of the Navajo Medicine Men. This is perhaps most evident in the totemic and mythological dialect of Pollock’s 1943 painting Guardians of the Secret. It is disputed among scholars as to what specifically led to Pollock formulating his ‘drip-painting’ method in 1947. However, it has been suggested that his witnessing of Navajo sand painting demonstrations at the New York Museum of Modern Art in 1941; along with his exposure to Navajo imagery while growing up in Arizona and California would greatly saturate the mind of the artist and may have proved significant in his artistic development.

Allegedly, Jackson Pollock was already interested in the works of Carl Jung when he began attending psychotherapy with Jungian psychoanalyst Joseph Henderson in 1939. During these sessions, it was agreed that Pollock could produce drawings and paintings as a foundation for the therapy; as he would reportedly remain very quiet. He would go on to produce eighty-three images in the two years he spent meeting Henderson for therapy. Following which, Henderson would state that Pollock’s attitude to his creative work had become ‘Shamanistic’ in nature. Pollock would continue psychotherapy with other Jungian-analysts after his sessions with Henderson ended in 1940.

An integral part of Jungian psychotherapy is the process of Individuation. According to Jung, the act of Individuation is the realising of the unconscious and thus its integration into our conscious lives: “If the unconscious can be recognised as a co-determining factor along with consciousness, and if we can live in such a way that conscious and unconscious demands are taken into account as far as possible, then the centre of gravity of the total personality shifts its position. It is then no longer in the ego, which is merely the centre of consciousness, but in the hypothetical point between conscious and unconscious. This new centre might be called the Self.”

For Jung, this integration of the unconscious includes the recognition and acceptance of the four fundamental archetypes: the Self, the Shadow, the Persona and the Anima/Animus. He believed that once one has incorporated these elements, they would be Individuated; or a properly functional individual– without fears or motivations hidden in the realm of the unconscious. Thus, the fundamental aim of Jungian therapy is to make the unconscious conscious.

As previously stated, Pollock would attempt this formally in his sessions with Henderson through his therapeutic drawings; though arguably his whole creative canon could be viewed as such. It is entirely possible to read his 1943 painting Moon Woman Cuts the Circle, for example, in purely Jungian archetypal terms. With its union of opposites; the masculine and feminine principles standing as symbols for the conscious and the unconscious respectively, while the ‘Moon Woman’ herself may be read as the Anima. Reaching deep into the collective unconscious, Jackson Pollock could be characterised as the contemporary shaman for post-war America; searching for the symbols of a lost innocence in the metaphysical annals of collective memory.

Carl Jung would write of the psyche of the artist in The Spirit in Man, Art and Literature:

“We would do well, therefore, to think of the creative process as a living thing implanted in the human psyche. In the language of analytical psychology this living thing is an autonomous complex. It is a split-off portion of the psyche, which leads a life of its own outside the hierarchy of consciousness. Depending on its energy charge, it may appear either as a mere disturbance of conscious activities or as a supraordinate authority which can harness the ego to its purpose.”

The universal elements of phenomenology and human experience, along with the themes of self discovery and transformation so deeply explored by Jung, armed Pollock and the abstract expressionists with the appropriate toolkit and motivation necessary to transcribe and integrate the symbolic language of the psyche. This in turn enabled them to alchemise a truer and deeper reflection of the twentieth-century, post-war individual.

“Art bears the same relationship to society that the dream bears to mental life.”

- Jordan Peterson

The McCarthy era milieu, in the years following the Second World War, was one of distrust, unease and censorship in the United States. The aftermath of the war irrefutably ushered in a thick social malaise that demanded a mass introspection; and the artists of the era turned inward in order to reconcile the soul of the century. The New York school of abstract expressionists were to be at the cultural frontier of self discovery, and provided a generation with the only appropriate imagery to reflect the age.

In 1943 Jean-Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness was published, and his brand of existential philosophy proved extremely popular, especially with the abstract expressionists; despite Sartre’s critique of the Freudian unconscious. Along with Martin Heidegger’s ‘Dasein’ (being-in-the-world) and ‘Thrownness’; Sartre’s discussion of ideas such as the absurdity, fluidity and ‘Angoisse’ or anguish of existence, and the inherent freedom of being were tenets that were sympathetic to the concerns of the New York School. The abstract expressionists, though not explicitly political, also shared with Sartre an interest in Marxist socialism.

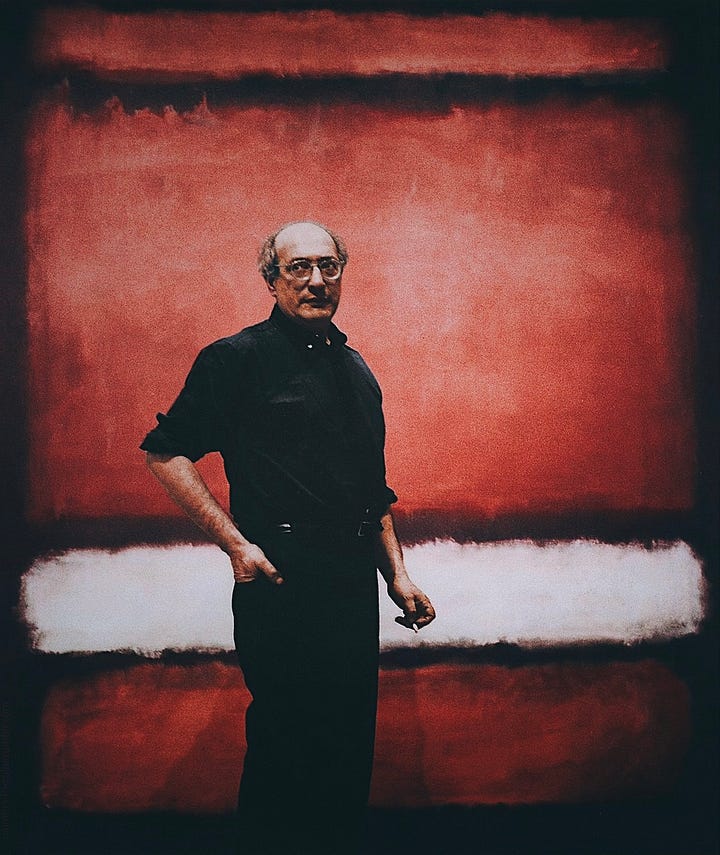

The work of the New York School colour field painters– namely Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still and Helen Frankenthaler (among others)- was perhaps rooted in this more contemplative and philosophical principle than the work of Pollock, de Kooning or Franz Kline. While the aforementioned action painters utilised the canvas as something approximating an arena for the unconscious contents and processes of the artist to manifest with physicality and gesture, the philosophical underpinnings of the colour field paintings allowed the viewer space for thought. The primacy of the unconscious subsequently fell from the creative act itself, to the recipient’s engagement with the painting(s).

Mark Rothko, the seminal colour field abstract expressionist, known primarily for his later works, would allow his visual language to evolve through various stages of development. However, his work of the early 1940’s would be heavily laden with symbolic and archetypal imagery, finding inspiration in Greek mythology and theological literature such as the Old and New Testaments; with several paintings such as Gethsemane (1944) referring to specific passages. It is entirely appropriate to suggest that Rothko was intentionally probing the collective unconscious during this period, in order to retrieve something eternal and integral to the human condition.

Rothko discussed these themes in a 1943 WNYC radio broadcast:

“If our titles recall the known myths of antiquity, we have used them again because they are the eternal symbols upon which we must fall back to express basic psychological ideas. They are the symbols of man's primitive fears and motivations, no matter in which land or what time, changing only in detail but never in substance… And modern psychology finds them persisting still in our dreams, our vernacular, and our art, for all the changes in the outward conditions of life. Our presentation of these myths, however, must be in our own terms which are at once more primitive and more modern than the myths themselves—more primitive because we seek the primaeval and atavistic roots of the ideas rather than their graceful classical version; more modern than the myths themselves because we must redescribe their implications through our own experience.”

Ultimately, however, Rothko would go on to reject the figure altogether. Concluding that figurative painting couldn't express the profound magnitude of tragedy inherent in the human condition, he would state "It was with the utmost reluctance that I found the figure could not serve my purposes… But a time came when none of us could use the figure without mutilating it."

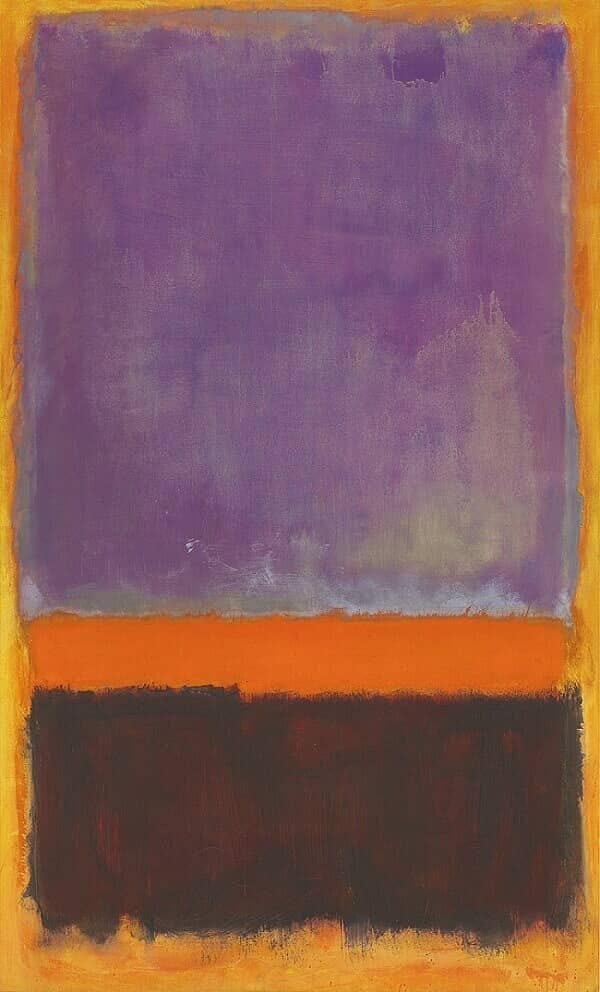

The following period of 1945-1946 saw Rothko’s development of a more abstracted idiom. The symbolic imagery of myth and archetype ebbed, and the subsidence of which left a quiet and more refined aesthetic. Through the use of diluted washes of pigment and layered glazes, the artist executed marvellous non-objective compositions populated with deep bands of colour, balanced structural weight and indeterminate openings. With their vibrancy, luminosity and unfathomable depth, these paintings act as windows to reverie. Rothko would refuse to expound upon the meanings of these works, or even conventionally title the pieces, in fear of ‘paralysing the viewer's mind’; as his apt retort would suggest: “Silence is so accurate”.

It is evident within these statements that Rothko was aware of the primacy of the viewer’s unconscious mind when interacting with his paintings. He sought to inspire something akin to a mystical or religious experience with his work, and we know thanks to the posthumously published The Artist’s Reality, Philosophies of Art, (2004) that he wrote privately that he wished to present “the unity of the ultimate by reducing all phenomena to the terms of the sensual.”

In 1958, Rothko accepted a commission to complete a series of paintings for the new Four Seasons restaurant in New York’s recently completed Seagram building. The artist wanted to take this opportunity to sicken New York’s elite echelons, and the resulting Seagram murals would lean into the architecture of Michelangelo’s Laurentian Library, reflecting its blocked windows and subsequent oppressive refusal of light and space. The dark palette and harrowing obscurity was an intentional assault on the unconscious minds of the restaurant’s patrons, theatrically expressing themes of “tragedy, ecstacy and doom.” In 1960, Rothko eventually cancelled the contract, confirming that the restaurant wasn't the appropriate environment for the paintings.

In the intervening years, Mark Rothko would feel a deep affinity for the Villa of the Mysteries murals in Pompeii. Not only due to their broad swaths of sombre colour and oneiric mystique; but their explicit worship of Dionysus was sympathetic to the artist’s temperament as a disciple of Nietzsche. Friedrich Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy (1872) is cited as among the most profound influences in the evolution of Rothko’s painting. The philosopher’s elucidation of the orderly and chaotic principles of art– characterised as Apolline and Dionysiac– makes the argument that the primal human ecstasy of the Dionysiac is the path to the sublime; yet Apolline order is the necessary antidote:

“We shall have gained much for the science of aesthetics when we have succeeded in perceiving directly, and not only through logical reasoning, that art derives its continuous development from the duality of Apolline and Dionysiac; just as the reproduction of the species depends on the duality of the sexes, with its constant conflicts and only periodically intervening reconciliations.”

Nietzsche’s view that art should dramatise the terror of existence was a sentiment that Rothko embodied until his eventual suicide in 1970. Vibrating between the radiant fibres of his canvases is “the most utter violence imprisoned in every inch of their surface.”

With the primal ecstasy of Pollock and the poignant meditation of Rothko, the abstract expressionists remain emblematic of the raw freedom of individuality and as profoundly expansive as the unconscious itself.

As Harold Rosenberg wrote in his seminal essay The American Action Painters (1952) “The American vanguard painter took to the white expanse of the canvas as Melville’s Ishmael took to the sea.” It is apt that Ishmael himself would soliloquise of whiteness: “Not yet have we solved the incantation of whiteness . . . Is it that by its indefiniteness it shadows forth the heartless voids and immensities of the universe and thus stabs us from behind with the thought of annihilation, when beholding the white depths of the milky way?”

Perhaps that ancient principle of order and chaos, the conscious and the unconscious; and the balance between, is what compels the artist– who eternally dwells on the threshold of the two– to fill the white void, and be the arbiter of that balance.

“The beautiful illusion of the dream worlds, in the creation of which every man is a consummate artist, is the precondition of all visual art.”

- Friedrich Nietzsche

Bibliography

Adolph & Esther Gottlieb Foundation. (n.d.). From the Archives: The Jewell Letters, ‘There’s no such thing as good painting about nothing’. [online] Available at: https://www.gottliebfoundation.org/blog/2021/9/28/from-the-archives-the-jewell-letters-theres-no-such-thing-as-good-painting-about-nothing.

Artchive.com. (2023). Guardians of the Secret (1943) by Jackson Pollock – Artchive. [online] Available at: https://www.artchive.com/artwork/guardians-of-the-secret-jackson-pollock-1943/.

Bigelow, J. and Ellis, D. (2013). Pollock the Shaman. [online] Donald Ellis Gallery. Available at: https://www.donaldellisgallery.com/files/The_World_of_Interiors-Pollock_The_Shaman.pdf [Accessed 11 Dec. 2023].

Cernuschi, C. and Pollock, J. (1992). Jackson Pollock, ‘psychoanalytic’ Drawings. Duke University Press.

courses.lumenlearning.com. (n.d.). 4.91: Modern, Postmodern, and Contemporary Art | HUM 140: Introduction to Humanities. [online] Available at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-fmcc-hum140/chapter/4-91-mid-late-modern.

Eliade, M. (2004). Shamanism : Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Princeton, Nj: Princeton University Press.

Ellis, D. (2013). Jackson Pollock and Native Art | Press | Donald Ellis Gallery. [online] Donald Ellis Gallery. Available at: https://www.donaldellisgallery.com/press/the-world-of-interiors-jackson-pollocks-obsession-with-native-american-art.

Freud, S. (1962). The Ego and the Id. New York: W.W. Norton.

Freud, S. (1995). The Interpretation of Dreams ; and On Dreams : (1900-1901). London: Hogarth Press.

Freud, S. (2005). The Unconscious. Penguin Classics.

Gamwell, L. (2000). Dreams 1900-2000 : Science, Art, and the Unconscious Mind. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press ; Bighamton, N.Y.

Jung, C.G. (1959). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton, Nj: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C.G. (1966). The Spirit in Man, Art and Literature. London: Routledge.

Jung, C.G. and Storr, A. (1999). The essential Jung : selected writings. Princeton, N.J. ; Chichester: Princeton University Press.

Kjellgren, E. (2021). Ubirr (ca. 40,000?–present). [online] Metmuseum.org. Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ubir/hd_ubir.htm.

Kuspit, D.B. (1993). Signs of Psyche in Modern and Postmodern Art. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lanset, A. (2017). Rothko and Gottlieb discuss, ‘The Portrait and the Modern Artist,’ on WNYC’s Art in New York | WNYC | New York Public Radio, Podcasts, Live Streaming Radio, News. [online] WNYC. Available at: https://www.wnyc.org/story/rothko-and-gottlieb-discuss-portrait-and-modern-artist-wnycs-art-new-york/ [Accessed 18 Dec. 2023].

Melville, H. (2001). Moby-Dick: or, The Whale. New York, New York: Penguin Books.

National Gallery of Art (2016a). Mark Rothko: Classic Paintings. [online] Nga.gov. Available at: https://www.nga.gov/features/mark-rothko/mark-rothko-classic-paintings.html.

National Gallery of Art (2016b). Mark Rothko: Early Years. [online] Nga.gov. Available at: https://www.nga.gov/features/mark-rothko/mark-rothko-early-years.html.

Nietzsche, F. (1993). The Birth of Tragedy: Out of the Spirit of Music. Translated by S. Whiteside. Penguin Publishing Group.

Rosenberg, H. (1952). The American Action Painters. [online] Available at: http://timothyquigley.net/vcs/rosenberg-ap.pdf.

Rothko, M. and Rothko, C. (2004). The artist’s Reality : Philosophies of Art. New Haven, Ct ; London: Yale University Press.

Sartre, J.P. (1999). Being and Nothingness : A Phenomenological Essay on Ontology. New York, Ny: Washington Square Press.

Sesar, D. (2023). How Did Carl Jung Influence Jackson Pollock’s Art? [online] TheCollector. Available at: https://www.thecollector.com/carl-jung-influence-jackson-pollock/.

Solomon, R. (n.d.). Identity and Freedom in Being and Nothingness | Issue 64 | Philosophy Now. [online] philosophynow.org. Available at: https://philosophynow.org/issues/64/Identity_and_Freedom_in_Being_and_Nothingness.

Spivey, V. (n.d.). Abstract Expressionism, an introduction (article). [online] Khan Academy. Available at: https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-1010/post-war-american-art/abex/a/abstract-expressionism-an-introduction.

Tate (n.d.). Mark Rothko: The Seagram Murals – Display at Tate Britain. [online] Tate. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/visit/tate-britain/display/jmw-turner/mark-rothko-seagram-murals.

Warburton, N. (2022). Everyday Philosophy: The links between Nietzsche and Rothko. [online] The New European. Available at: https://www.theneweuropean.co.uk/everyday-philosophy-the-links-between-nietzsche-and-rothko/.

Wolfe, S. (2019). Art Movement: Abstract Expressionism. [online] Artland Magazine. Available at: https://magazine.artland.com/abstract-expressionism [Accessed 18 Dec. 2023].